This month marked my first year in Japan: My Japanniversary.

My first year as an expatriate felt a lot like a bad prom date. I was incompetent, needy, never quite sure where to put my hands.

Japanese culture seems particularly prone to this kind of stress. Everything requires paperwork and stamped approvals, which you can’t fill out on your own. Maps, even online, are impossible to read. You have no idea what’s on menus, how to do laundry, where they keep the cereal in grocery stores (the dessert aisle, it turns out). You don’t know when to bow, how to dodge bikes on the sidewalk, how to sign up for a mobile phone or access the Internet.

So you ask for help. And you keep asking, for 365 days. As those days go by you wonder if you will ever be able to do anything on your own, again, for the rest of your life.

Then you do.

Japanxiety

I can see how Japan has seeped in over the year. It’s in superficial things, like reflexively bowing or apologizing constantly to people and inanimate objects. But it’s subtle, too.

There’s no personal space in Japan and it wears on you. You’re packed into small trains, or sitting next to colleagues who ask you about everything you’re doing for 8 hours a day. You’re constantly being offered help or being watched or weirdly ignored.

I’ve become more claustrophobic and more reclusive than I already was, a little overwhelmed by large social situations, a little more desperate for a few minutes of occasional invisibility.

Living abroad is a humbling experience. The challenge is finding ways to reclaim your dignity in a culture where autonomy isn’t an important aspect of anyone’s dignity.

The Alternative to Independence

Get three male expats together and you can set a timer on how long it takes for someone to mention the gym. Unlike everything else in Japan, your body is completely yours to do what you want with.

You want to feel empowered? Lift weights. Climb a mountain. Start running. No one is going to stop you. Others pick up musical instruments or martial arts, photography, or alcoholism. I’m cultivating a mild addiction to social media and their endless opportunities for self-definition.

There’s a tendency in Japanese culture to embrace hobbies in hardcore ways. That’s definitely seeped into my life.

Culture Shock

Culture Shock extends way beyond being freaked out by robots at the mall or how expensive apples are. It’s actually a distinct kind of mild trauma; with phases that flow in and out over time.

- The Honeymoon Phase, where the mall robot is cool and cute and weird and awesome and OMG JAPAN!!!!!1

- The Negotiation Phase, where you don’t understand why you have to use a f@%king robot to find out where the f@%king shoe store is and you just KNOW the f@%king shoe store isn’t going to have your f@%king size.

- The Adjustment Phase, where you learn how to get the robot to work properly and you get that the robot is doing its best to help you out.

- The Mastery Phase, where you don’t even think about the robot as anything out of the ordinary.

These phases are in no particular order, and working your way out in one aspect of a culture is no guarantee that you’ll work it out everywhere. I can ride a train with ease but I can’t get a decent haircut.

Some people adapt, others don’t. Either way, along the way to rejecting the culture and heading home or adopting the culture and staying forever, you’re gonna get cranky and you’re going to feel a little helpless.

That’s just the nature of culture shock. It’s traumatic.

Japan’s Worst Tour Guide

My Japanniversary coincided with an ambitious, two-week-long blitzkrieg tour of Japan with my best friend from the States. As the only Japanese speaker (a relative term) I was responsible for planning the itinerary, making reservations, scheduling trains, communicating to taxi drivers and restaurant servers, asking for directions and finding vegetarian food in Japanese.

I made a lot of mistakes. There were social ones, thanks to my Japanese cultural indoctrination (“Why are you apologizing for the rain?”) and functional ones (I returned three times with the wrong ticket to the same station agent in a rural Kyushu train station; his annoyance was visible, and this is Japan).

You get kind of beat up. But then something happens. You’re in the backseat of a taxi with a driver saying “ne” when he means “ka”, but somehow you can tell he’s warning you that the rope cars on the mountain you’re planning to hike are closed. You’re lost on the side of another mountain and some guy tells you where to go and somehow you understand him.

My grammar was awful; I used weird particles and awkward constructions. But with the natives, in real situations, I stopped getting puzzled looks and started getting answers.

I started getting to the mountain, started catching the right buses, started ordering exactly what I wanted to eat.

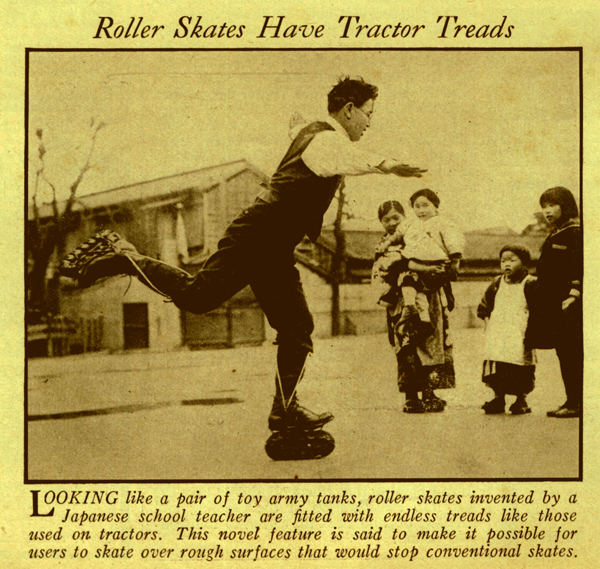

On Rollerskating in Japan

The day after my friend left, I was feeling down. Despite traveling for two weeks straight, I wanted to get out of the house and eventually ended up with some expats waiting to talk about weightlifting at a sports and gaming complex.

After some video games, my introversion finally kicked in and I snuck off to the roller skating rink.

I used to roller skate as a kid. Never went rollerblading, though. Since the 8th grade, I’ve left rollerblading to middle-school kids with rat tails. I wanted skates. I wanted dorky ’50s drive-thru waitress gear, and I found them: Pink, Japan size 28, four wheels per shoe.

I totally expected to get out there and fall. I expected to get out there and be outperformed by 7-year-olds. I expected it to be a little like everything I’ve ever tried to do in Japan.

But I remembered how to skate. It was instinctive. Shift weight from ankle to ankle. Twist a bit when you go around a curve. Lean a little to accelerate. I was wobbly at first but picked up speed.

There were some hot shots on the floor and yeah, maybe some of them were 12-year-olds. But there was also an obstacle course of falling teenagers, middle-aged moms with no clue how to move and 20-year-old guys losing control and crashing into walls.

But not me. I was moving. I was in control. And I was having fun.

Just 352 days left.

Notes

The lead Roller Skating image comes from a June, 1936 issue of Popular Science magazine.

Like this post? You can follow This Japanese Life on Facebook or @owls_mcgee on Twitter, for at least 352 more days.

Happy Japanniversary! Your post makes me remember mine fondly, and I love the way you summed up the stages with regards to the robot. That “mastery phase” is beautiful when you realise you’ve got there, isn’t it?

Good luck with the roller skating! ;)

Hey thanks! Do you remember when you finally felt like you were “clicking” with Japanese culture?