This week, we’re sharing a guest post from expat writer and J-blogger, Baye McNeil, aka “Loco in Yokohama.” This excerpt, from his eponymous book, is about kids learning English in some unconventional ways. It contains some spicy language and situations, so turn off your child’s Internet if you’re worried.

At first, I was only teaching to finance my adventure in Japan. I worked at a franchise English school, and I took it as seriously as I would working at a hamburger franchise — basically the culture the company inspired with its business antics and treatment of its staff. Eventually I got fed up with doling out English burgers for a living and moved on to the public schools of Yokohama.

While teaching public school kids as an ALT (Assistant Language Teacher) also had that same sense of a fast food education, I realized that I had the power to change it. And once I made that decision, it became a much more rewarding experience for myself, and more importantly, for the kids.

The greatest reward I’ve received from teaching and spending everyday with these little founts of energy, optimism and enthusiasm, was that being in that environment rekindled a fire in me that the ignorance, intolerance and plasticity of life in Japan, up to that point, had begun to douse. I was a breath away from apathy and from writing Japan off as an irredeemably lost cause.

But these kids saved me from the darkness that threatened to swallow me whole. My latest book, called Loco in Yokohama, is all about my allies in this battle, specifically the people of Yokohama, the remarkable educators I teach with, and these amazing kids.

The following excerpt is an example of the energy I’ve been blessed with here in Yokohama. It’s kids like the two boys I’m about to introduce that made this transition possible.

Manzai of the Onani Brothers

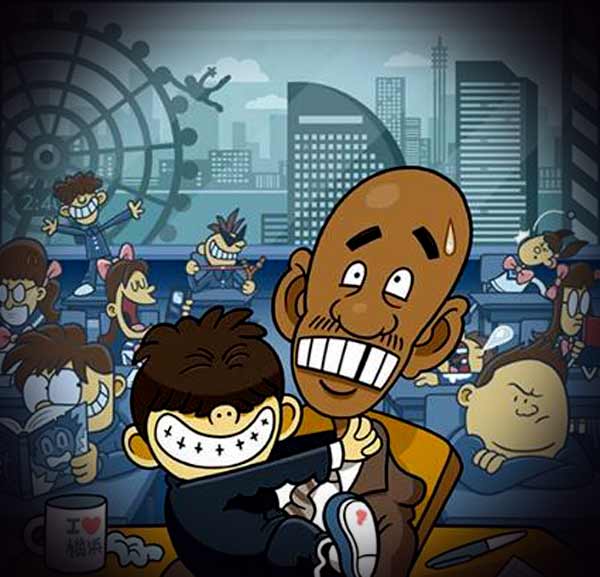

I had two third-year students who, over the course of three years, had made it their prime directive to shock and awe me, and their escapades escalated with each passing year. Just try to imagine Jackie Gleason and Art Carney of “The Honeymooners” fame, then picture them together as junior high school students in the 21st century. Now make them Japanese. The resulting picture would probably resemble Yuuji-kun and Kintarou-kun. Yuuji was kind of chubby, but with the pep and agility of an athlete. Kintarou was the straight man who could set anyone up for a prank with the skill of a seasoned pantomime.

I knew from the first time I met them, back when they were first-year students, that they would be inseparable and a handful. I’d learned from their classmates that they had been a popular duo since elementary school, so, for the two of them, junior high school meant some new audience members—classmates coming from other elementary schools—and fresh teachers to impress with their stagecraft. And they were up to the task. Both just happened to have IQs that were off the charts, so not only were they the class clowns, but they also aced tests in almost every subject, I’d learned.

English was a new challenge, however. They came to the school with as much exposure to English as the other students in the class—little to nil. But, they took an immediate liking to me, and began from day one demonstrating an intense interest in learning about me and this language I spoke.

And, by intense, I mean they took the initiative like you wouldn’t believe. They were classic examples of why I ceased assuming anything about what Japanese people know or don’t know, or were capable of, especially students. They started by not watching, but studying English movies and TV shows, especially comedies and rather racy stuff, and stopping me in the hallways to explain to them the meaning of words or running the expressions they’d learned by me to see if they had gotten it right.

That first year, I remember Yuuji stopped me in the hallway one day and said, “Good Morning Loco-sensei! How are you?”

“I’m fine, thank you, and you?” I replied, like I did a thousand times a week to my kids.

“I’m fine, thank you.”

It was just as I had taught him and his classmates a few weeks earlier, straight from the textbook. And I was about to praise him on his voice and diction when I noticed Kintarou coming our way. Yuuji was looking in my face, the perfect expression of a student awaiting a pat on the head, when he turned and saw Kintarou like he’d sensed his approach.

Suddenly, Yuuji burst out yelling, “You son of a bitch! I ought to kick your ass!”

Kintarou hissed like a snake and assumed a battle-ready stance. “You just try it, you fat fuck. I’ll wipe that stupid look off your face!”

I stood there with my mouth open in shock. I’d never seen such aggression from Japanese people except in movies or maybe a K-1 fight. Suddenly, they were grappling with one another, and Yuuji got Kintarou in a bear hug and was squeezing him, pumping him from the rear like a steroid-addled troglodyte, and yelling, “How do you like that? Huh? How do you like that?”

An audience of students started to draw near, but no one intervened. They just stared half-amused and half-shocked.

Kintarou’s face had turned red and he looked as if at any moment he might pass out so I stepped over and told Yuuji to let him down.

In English.

That’s when I realized that I’d understood perfectly everything they’d said because they, too, had been speaking English!

Yuuji was watching my face and started laughing as he set Kintarou down. Kintarou still had the crimson hue of someone who had just got the life squeezed out of him, but he was laughing, too.

Two professionals.

I was speechless. They both nodded like they understood what I hadn’t said — ‘you guys are gifted!’

Kintarou and Yuuji kept this up for their entire first year of school. Their conversational English was still at a very basic level, but they were learning many natural English expressions on their own, and incorporating them into their everyday conversation. Each expression had been chosen for its shock value and they rarely failed. I’d ask them, as I ask all students every day, “How’s the weather today?” Most students would say sunny, rainy, cold, or cloudy. Some students might remember to say “it’s” before the weather condition. Most didn’t, regardless of how many times I tried to re-wire their minds on the matter.

Yuuji would make my day and say something like, “It’s cold as fuck!” and Kintarou might say, “Who cares? We’re inside!” With those two, you never knew what you were gonna get. Even when I’d expect the unexpected, they’d figure out a way to catch me off guard, or they’d do nothing and have me second guessing everything.

In their second year, they took to hanging out around the bathroom between classes with a mob of fans and friends. When I’d walk past, they’d grab me by the crotch and try to drag me into the bathroom. Like most Japanese kids, they had no qualms about playing grab-ass and possessed no homophobic hang-ups like we had back when I was a junior high school student. So, I was subjected to all kinds of sexual pranks when I walked by. One time, I let them drag me into the bathroom against my better judgment, just to see what they were up to in there. Four of them pulled me in where another ten or so were standing around like a scene from any American school movie— only no one was smoking, drinking, writing graffiti on the wall, or anything like that. It was just a bunch of kids hanging out in the toilet.

One time I was flung into this mix and the students who were already in the bathroom froze guiltily or jumped about like I’d caught them doing something. I looked hard, but I couldn’t see, hear, or smell anything amiss. If shoving their fingers up my ass (called “kancho”) was OK, who knew what else went on with these kids when no adults were watching? I certainly didn’t.

“Nani shiteiru?” (What are y’all doing?)

“Nani mo nai yo.” (We ain’t doing nothing.)

I knew the Japanese word for masturbation: “Yappari. Onani shiteiru deshou!” (Probably whacking off in here!)

“Chigau!” (Hell no!)

Since I’d gotten a rise out of them, I figured I must have struck close to home.

Of course, Yuuji thought this was the perfect time for some hijinks. He started miming some sexual gestures toward Kintarou, while Kintarou looked perfectly like he wasn’t experiencing intense pleasure.

“The Onani Brothers!” I called them, and they loved it. The name stuck.

This is an excerpt from Loco in Yokohama, Baye McNeil’s book about his experiences teaching English in Japan, which is available in print or as an e-book on Amazon. If you’d like to read more from Baye, he writes regularly over at Loco in Yokohama.

This is an excerpt from Loco in Yokohama, Baye McNeil’s book about his experiences teaching English in Japan, which is available in print or as an e-book on Amazon. If you’d like to read more from Baye, he writes regularly over at Loco in Yokohama.

Reblogged this on distant drumlin.

Pingback: This Japanese Life!! | Loco in Yokohama

This was adorable! What a great story!